Using Social Media Data in Research—Whether You’re in English Lit or Information Science

I’m excited to share that my essay, “The Challenges and Possibilities of Social Media Data: New Directions in Literary Studies and the Digital Humanities,” was just published open-access in the latest volume of Debates in the Digital Humanities 2023.

In this essay, I write about two things:

- how book-related social media data (e.g., Goodreads ratings, BookTok videos, fanfiction stories, r/books Reddit memes) has enabled all kinds of cool new research related to contemporary readers, literature, and culture;

- how social media data also seriously challenges traditional ways of doing research—especially but not exclusively in the humanities and literary studies—and how it demands new approaches and considerations of user privacy and ethics.

If you’re interested in readers, reception, or how scholars are using digital humanities approaches to study the life of texts, I hope you’ll check out my full Debates in the Digital Humanities essay. In the first half of the essay, I sketch out the DH subfield of “computational reception studies” and show how social media data resembles earlier forms of reception data featured in DH work, such as 19th-century library checkout records and 20th-century book reviews.

But in this blog post, I want to briefly summarize a few of my main recommendations for working with, sharing, and citing social media data in research because I get asked about these issues a lot.

I also want to address a couple of major developments in the social media world that have taken place since I finalized copyedits on the essay in October 2022 — like the takeover of Twitter by a̶ ̶r̶i̶g̶h̶t̶-̶w̶i̶n̶g̶ ̶t̶r̶o̶l̶l̶ Elon Musk, who quickly shuttered the Academic Twitter API, and who made the regular Twitter API so expensive that it’s basically shuttered, too.

These changes have rocked the social media research community, and they complicate at least one of my recommendations in the essay, so I wanted to provide an update on my thinking and the state-of-the-field here.

via The Verge

Most of my recommendations for working with social media data are collated from or inspired by the work of other researchers I admire — including Moya Bailey, Sarah J. Jackson, and Brooke Foucault Welles; Deen Freelon, Charlton D. McIlwain, and Meredith D. Clark; Dorothy Kim and Eunsong Kim; Brianna Dym and Casey Fiesler; and members of the Documenting the Now project.

The reason that these researchers and the best practices that they espouse or model in their work are so important is because there aren’t clear laws or guidelines that dictate how you’re supposed to work with social media data responsibly.¹

IRBs, or institutional review boards, are administrative bodies that evaluate and approve the ethical dimensions of research involving human participants (IRBs are required at U.S. institutions that receive federal research money; institutions outside the U.S. have their own equivalents), but IRBs have mostly washed their hands of social media research. They’ve largely determined that, if the social media data is “public,” then the research falls outside their purview.

Do you need IRB approval to work with social media data? is one of the most common questions that I hear from people who are new to this area. And the answer to that question is basically: it depends; it’s safest to apply and get an exemption; but probably no.

Penn Social Behavioral Research on social media data and IRBs

When I first started doing social media research (collecting tweets about the writer James Baldwin with the Twitter API), I was a few years into an English Literature PhD program, and I felt especially lost about the best ways to collect and share tweets or cite them in published articles, because literature professors don’t often do “human subject” research or work with IRBs or include this kind of training in their graduate programs. But since the IRB has largely abdicated its responsibility with regard to social media research, it turned out that social scientists and scientists were basically in the same boat, too. And we’re all still in that boat.

That’s why I’ve chosen to turn to the model of the scholars and projects mentioned above and discussed below. I believe that these researchers and their work are particularly useful not only because their work is exemplary but also because their work focuses on the data of marginalized or otherwise vulnerable communities, such as Black activists and LBGTQ fanfiction writers. Centering research on these communities can, I think, help us develop social media research best practices that consider the experiences of those disproportionately subject to risk online as a baseline.

How should researchers engage with the online communities whose data they computationally collect and analyze?

As OpenAI’s massive scrape of internet data has proven, it’s not only possible but incredibly common for companies, researchers, and regular people to collect users’ personal data without their permission and knowledge. Equally worrisome, it’s just as common for the same parties to lack knowledge about the users whose data they collect.

As Bergis Jules, Ed Summers, and Vernon Mitchell put it in their white paper for Documenting the Now (a project that helps develop tools and practices for ethically archiving social media data):

the internet affords the luxury of a certain amount of distance to be able to observe people, consume information generated by and about them, and collect their data without having to participate in equitable engagement as a way to understand their lives, communities, or concerns.

For these reasons, they and other scholars argue that researchers should engage with and be knowledgeable about the communities whom they are studying and collecting data from — whether through conversation, collaboration, interviews, or ethnographic approaches.

By directly engaging with online communities, researchers can make better, more informed, and more context-dependent decisions about other parts of the research process, such as whether to cite a specific user in a published article (more on that below).

For example, in Brianna Dym and Casey Fiesler’s extremely useful best practices for studying online fandom data, they recommend that researchers who are not familiar with fan communities “spend time [in online fandom spaces] and take the time to talk to fans and to understand and learn their norms,” not only to learn more about the community but also to become more “mindful of each user’s reasonable expectations of privacy, which may be dependent on the community or platform.”

They further underscore that making connections with individual users is possible even for large-scale, data-driven research:

Even for public data sets in which individual participants might number in the tens of thousands to the millions, it might be possible to talk to some members of the target population in order to better understand what values and concerns people might hold that would deter them from consenting to their data being used.

Here are a few concrete examples of this kind of mixed-methods (quantitative/qualitative) approach to studying and engaging with social media communities in action:

- In Moya Bailey’s research on the hashtag #GirlsLikeUs, which was created by trans advocate Janet Mock, Bailey sought Mock’s permission to work on the project before it began, and she collaborated with Mock to develop her research questions and determine the project’s direction. Though Bailey’s research included data collection and quantitative analyses, it was also shaped by a consenting collaborator who was part of the community being studied.

- In Bailey’s 2020 book with Sarah J. Jackson and Brooke Foucault Welles, #HashtagActivism: Networks of Race and Gender, they similarly frame social media users as collaborators, and they pair each chapter of the book with “an essay written by an influential member of a particular hashtag activism network.”

- Along similar lines, Deen Freelon, Charlton McIlwain, and Meredith Clark used large-scale network analysis techniques to study 40 million #BlackLivesMatter (BLM) tweets in their report “Beyond the hashtags: #Ferguson, #Blacklivesmatter, and the online struggle for offline justice.” But they also interviewed and talked to dozens of BLM activists and allies “to better understand their thoughts about how social media was and was not useful in their work.”

How should researchers cite social media users in published research?

If you want to include or quote a social media post in your published article, should you cite the author, anonymize the author, paraphrase the post, or do something else? This is another common question that I hear as a social media researcher, and I think it’s an especially important one for humanities scholars, who often include and analyze specific examples of texts in their work (as opposed to computer science researchers, for example, who often work with aggregated representations of data).

Before going any further, I want to head off anyone who’s about to spout the erroneous but distressingly common argument that you can do whatever you want with social media data if it’s “public” — that is, if it’s published openly on the internet by a public account. Dym and Fieseler (and many other scholars) have worked hard to show that this argument is a load of hooey (as my grandma would say). They argue that privacy on the internet is contextual. Your expectation of privacy on Twitter (or X) is going to be very different if you’re a celebrity versus a regular person with 50 followers. And violating those expectations can have serious consequences, as I’ll explain below.

I helped @cfiesler make memes for her ethics class and came up with this gem pic.twitter.com/zGUYPtusaQ

— Dr. Brianna Dym (@BriannaDym) January 23, 2020

I showed this meme to my students, and now it lives rent-free in my brain.

So if you’re including or quoting users’ posts in published scholarship, coming up with a citation strategy is imperative.

Many people think that anonymizing social media posts is a good citation strategy that protects users’ privacy. But it’s not.“Even when anonymized by not including usernames, content from social media collected and shared in research articles can be easily traced back to its creator,” as Dym and Fiesler assert, drawing on a study by John W. Ayers and colleagues. Basically, you can google the text of a social media post and find the original post, context, and its author extremely easily.

The other big problem with anonymization is that it robs users of authorship. Creators deserve intellectual credit for what they create and publish, as Amy Bruckman and others have maintained.

So, anonymizing posts is not a good strategy, and explicitly citing the author of a post is ideal. But citation can be tricky, too. In some cases, it can even be dangerous to cite authors, especially if you do so without their knowledge and permission. Why? Because citing social media users in a new context can expose them to new and unexpected audiences, which can lead to unwanted attention, harassment, doxxing, personal and professional complications, and other negative outcomes.

For example, the Documenting the Now project—which has led social media archiving efforts related to the Ferguson protests, Black Lives Matter, and other social movements—discusses how “activists of color . . . face a disproportionate level of harm from surveillance and data collection by law enforcement,” and thus amplifying their words or actions (as documented through social media) might put them in danger, even more so than the average social media user.

In a similar vein, when Dym and Fiesler asked LGBTQ fanfiction writers and those with LGBTQ friends in the community how they felt about researchers or journalists citing their stories, they expressed many concerns, including the concern that “exposing fandom content to a broader audience could lead to fans being accidentally outed.”

For these reasons, researchers who wish to cite specific social media posts in published research should make their best effort to contact the authors and seek explicit permission to use the posts. But there are exceptions. If a user is a public figure, like Joe Biden, or if a post has already reached a wide public audience, like a viral TikTok video, then I personally don’t think that getting direct permission is necessary. However, it can be difficult to draw a line about who counts as a public figure or what counts as reaching a “wide public audience.”

In their “Beyond the Hashtags” report, Freelon, McIlwain, and Clark offer a few concrete examples of these “reasonably public” thresholds (as I like to think of them). Freelon et al. chose to only cite tweets that met at least one of the following criteria: the tweet had been retweeted more than 100 times; the tweet had been published by an officially verified Twitter account; and/or the tweet had been published by a Twitter account with more than 3,000 followers (placing a user in the top one-percent of the most followed Twitter accounts at that time). Additionally, they did not include the actual text of tweets in their report and only included links to the tweets, essentially enabling users to delete their tweets and remove themselves from the study. Devising these kinds of thresholds can be challenging and very subjective, but they can also be helpful for guiding the focus of a study away from obscure content and toward matters of genuine public interest and concern.

Frustratingly, Elon Musk’s drastic changes to Twitter have also impacted researchers’ ability to devise some of these thresholds, since he radically altered X’s “verified” user system. While in the past Twitter would “verify” a user by internally determining that their account was of “public interest” (a process that had its own flaws, to be clear), now this status is exclusively offered to users who pay for an X Premium monthly subscription. So today, X’s verification system doesn’t tell you anything except who’s paying for X.

Sometimes, of course, there are cases when a researcher might want to include a social media post in a publication, but it does not meet these reasonably public thresholds, and its author cannot be reached for comment or to grant permission. What to do then? In these cases, Dym and Fiesler recommend paraphrasing posts in such a way that they are not traceable back to the original post or ethically “fabricating” material in ways that Annette Markham has advocated and described, such as by creating a composite account of a person, interaction, or dialogue. These strategies may seem foreign and potentially even a little blasphemous to some humanities scholars, especially those who are trained to attend closely to texts and all their nuances. But if these adaptations are necessary to protect users in a given situation, then they obviously need to be embraced. (Basically, lit scholars, we will need to get over ourselves.)

What about if you’re studying social media users who you are critical of, such as fascists or white supremacists? This a question that I did not address in my Debates in the Digital Humanities essay, but I just wanted to raise it briefly here because I think it’s super important. In many ways, I think the best practices I’ve outlined above could still be applied successfully in these cases. If a post is shared by a prominent figure or has reached a wide audience, it’s fair game, and if it doesn’t reach those thresholds, and you can’t get in touch (or don’t want to get in touch) with the author of the post, perhaps you could paraphrase it. (Because of course it could be dangerous to directly contact a fascist or white supremacist and notify them about your involvement in research scrutinizing their behavior and beliefs, and it could be particularly dangerous depending on your identity.) But should you cite the author of such a social media post in full without the author’s permission just because you disagree with them or even disavow them? I’m not sure. Perhaps you could make the case that studying fascist or white supremacist online communities (or whatever communities) is such a matter of public significance that it would justify this choice, that its significance might be akin to a post having reached a wide public audience. But again, I’m not sure. This is an issue that I continue to struggle with, and I would love to hear more about what other people think and what strategies people have developed to address these issues.

How, if at all, should researchers share users’ data?

While sharing data is a vitally important part of the research process—enabling reproducibility, enhancing evaluation, and increasing accessibility—sharing social media datasets in responsible ways can be very challenging. Social media datasets contain a lot of potentially identifiable information about users, so sharing this kind of data is often explicitly prohibited by platforms’ Terms of Service, and beyond that (because of course we don’t let platforms tell us what’s ethical and what’s not) it’s often considered a privacy violation that can lead to negative consequences for users, such as doxxing, harassment, and other adverse outcomes like those discussed above.

One potential strategy for mitigating these harms is to share social media datasets in ways that enable users’ “right to be forgotten”—that is, to enable users to remove themselves from the dataset whenever they want. Usually, this means introducing some kind of time lag into the dataset sharing/retrieval process. For example, a researcher might share the code that they used to scrape TikTok posts but not the posts themselves, enabling others to recreate the dataset but not include any posts that have been deleted or removed.

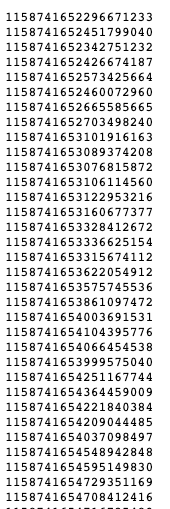

Perhaps the best known and most institutionally supported example of this kind of approach was Twitter’s “tweet ID” sharing format—a format that Elon Musk has virtually destroyed since I published my Debates in DH essay. A tweet ID is a unique identifier that is associated with every single tweet that’s ever been tweeted. Basically, it’s a unique string of numbers — e.g., 1702444061657841919 —that links back to a full, richly embodied tweet, with its text, author, URL, publication date, images/videos, and all its other juicy metadata.

Before Musk’s takeover of the platform, you could pass a list of tweet IDs to the Twitter API and download full datasets for the tweets that they referenced—a process known as “hydrating” tweets. The most important part was that you could only download data for tweets that still existed. Because a tweet ID will only link back to a tweet if it has not been deleted or if its account has not been made private or suspended, etc. For these reasons, Ed Summers, the technical lead of the Documenting the Now project, has suggested that tweet IDs advance an implicit ethical position by allowing users “to exercise their right to be forgotten.” By deleting a tweet or making their account private, users can remove themselves from all future versions of the data.

Twitter’s policies have long forbidden people from publicly sharing full datasets of tweets, but it has allowed people to openly share tweet IDs. And until recently (as recently as November 18, 2023), academics were even explicitly permitted to share as many tweet IDs as they wanted:

If you provide Twitter Content to third parties, including downloadable datasets or via an API, you may only distribute Tweet IDs, Direct Message IDs, and/or User IDs (except as described below). We also grant special permissions to academic researchers sharing Tweet IDs and User IDs for non-commercial research purposes.

In total, you may not distribute more than 1,500,000 Tweet IDs to any entity…within any 30 day period unless you have received written permission from Twitter…Academic researchers are permitted to distribute an unlimited number of Tweet IDs and/or User IDs if they are doing so on behalf of an academic institution and for the sole purpose of non-commercial research.

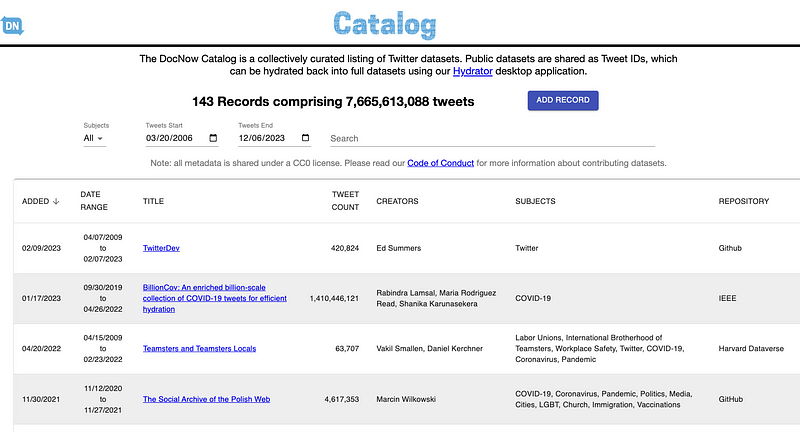

Because of this institutional support and its inherent “right to be forgotten” capacities, many researchers chose to share their data as tweet IDs in the last decade or so. The DocNow project even created a catalog of tweet IDs, which now hosts more than 7 billion of them—linking back to full Twitter datasets about COVID, Donald Trump, Toni Morrison, natural disasters, celebrities, protest movements, the alt-right, and many other important subjects. Summers also created a widely-used GUI application called “Hydrator,” which conveniently allowed people to download tweets from lists of tweet IDs via the API but without ever touching the command line or writing a single line of code.

DocNow Catalog (https://catalog.docnow.io/)

But today, sadly, Musk’s dismantling of the API and other radical policy changes have robbed DocNow’s incredible Catalog and Hydrator app and even their Twitter collection tool twarc of much of their usefulness. (The DocNow team has written about the demise of these tools here, offering their own perspective on paths forward.) Because today, with the current “Free” tier of the Twitter API, you can’t hydrate any tweet IDs at all. And with the $100-a-month “Basic” tier and the $5,000-a-month “Pro” tier, you can only retrieve (“pull”) 10,000 tweets and 1 million tweets per month, respectively. This is a severe curtailing of what used to be possible. Seven years ago, when I was a graduate student, I was able to hydrate 30 million tweets in under a week with only free access to the Twitter API. The tweet IDs that I hydrated were publicly shared by Freelon, McIlwain, and Clark from their “Beyond the Hashtags” report, and their generous data sharing was what made it possible for me to do the research that would become my first published article. I didn’t have the funding or capacity at the time to get this data in any other way. And it’s sad to me that today’s graduate students, as well as other researchers with limited funding, will not be able to benefit from the same kind of data sharing.

In addition to the severe curtailing of the API, X also recently (again very recently, since November 18, 2023) changed its developer policy with regard to tweet IDs (which they now call “post IDs”). Academics are no longer permitted to share as many post IDs as they want, and in fact there are new clauses that suggest that, before sharing post IDs, X must explicitly approve of the research related to the post IDs in writing (unclear if this approval includes having previously been approved for a Academic Twitter API account):

If you provide X Content to third parties, including downloadable datasets or via an API, you may only distribute Post IDs, Direct Message IDs, and/or User IDs (except as described below).

In total, you may not distribute more than 1,500,000 Post IDs to any entity…within any 30 day period unless you have received written permission from X….Academic researchers are permitted to distribute Post IDs and/or User IDs solely for the purposes of non-commercial research on behalf of an academic institution, and that has been approved by X in writing, or peer review or validation of such research. Only as many Post IDs or User IDs that is necessary for such research, and has been approved by X may be used.

So what will become of the billions of tweet IDs shared by researchers that are now basically inaccessible through the API? And how else can we responsibly share Twitter data — or other kinds of social media data?

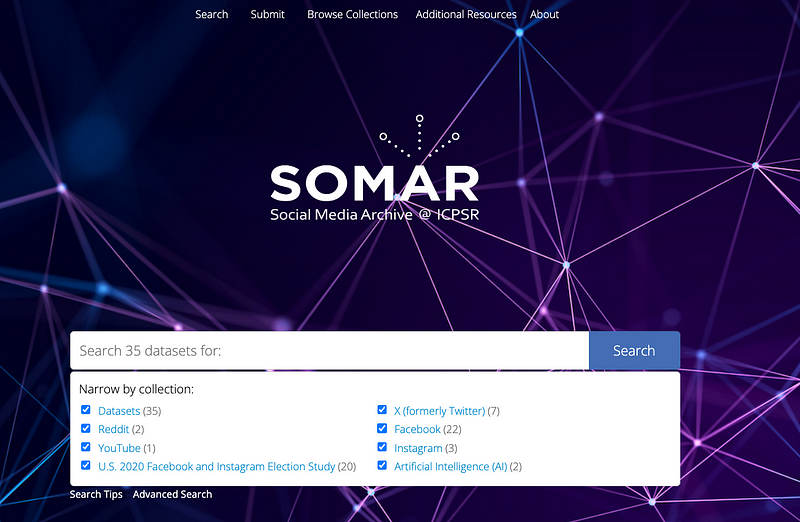

Another strategy for sharing social media datasets is to use institutional repositories like the new Social Media Archive (SOMAR), housed by the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) at the University of Michigan. SOMAR is promising because it allows researchers to place restrictions on the datasets that they share, so it’s possible to deposit and share a social media dataset but require anybody who wishes to access the data to submit an application that might include: proof of affiliation with an academic institution and a terminal degree, a summary of the research that they intend to do, proof of IRB approval from their own institution, a signed restricted data agreement, and more. Additionally, when depositing data into SOMAR, researchers can choose to restrict access to a Virtual Data Enclave (VDE), so that others can’t actually download the data or take the data anywhere beyond the platform. (It’s also possible to make data publicly available for direct download, or to make data available for direct download with only a login to a SOMAR account.) So perhaps researchers who previously shared their Twitter data as tweet IDs on the DocNow Catalog might instead deposit their Twitter datasets into SOMAR with appropriate restrictions.

SOMAR (https://socialmediaarchive.org/)

Interestingly, SOMAR is also supported by a $1.3 million gift from Meta, and Meta has just unveiled a new academic research API that is exclusively available through SOMAR’s Virtual Data Enclave (VDE). They also announced that ICPSR and SOMAR will handle all of the applications for research access to Meta’s new API. This partnership introduces a new model for academic social media research, attempting to close the gap between Big Tech social media and the academy, and eliminating the need to share data by never letting the data leave in the first place. The fact that Meta has so much unilateral power in determining what data researchers can access through this API/platform—as well as what researchers can do with that data—is concerning. When Meta has provided data to researchers in the past and asked researchers to trust them without transparency, it has not worked out well. But who knows what will happen with this new partnership.

Despite these concerns, I am still interested in and curious about SOMAR’s future. The repository addresses a pressing need in the field that is not being addressed in very many other places. Of course, there are additional drawbacks to sharing data in repositories like SOMAR. For example, some of the restrictions that can be placed on data are exclusionary to those who are not academic researchers with terminal degrees, likely making some data unavailable to the communities who actually created it. (Enabling communities to access and control their own data has long been a goal of the DocNow project, and they recently wrote about the benefits of diversifying “who can use web and social media archiving tools to create data collections…beyond academic researchers and the handful of archivists at academic and national libraries”). Also, these kinds of dataset deposits do not inherently enable users’ right to be forgotten as some other data sharing approaches do. But for now, it is still better than most alternatives (like openly publishing sensitive user data or allowing valuable archives of social movements to die on old computers), so I think it’s worth paying attention to.

The world of social media changes rapidly, as the last year has shown us. (I mean, for real, providing updates on all of Elon Musk’s antics has made this update almost as long as my original essay.) To keep pace, the conversation about working with social media data will need to change and evolve, too. But I think the model demonstrated by the researchers discussed above—which emphasizes actual engagement and conversation with social media users, explicit permission with regard to quotation and citation of posts, responsible data sharing practices, and a prioritization of the most vulnerable—can provide a solid foundation for the future. And in that future, I think that researchers will need to be sure to develop social media data infrastructures and approaches that are distinct from, and even explicitly opposed to Big Tech platforms, even as we find ourselves sometimes necessarily collaborating with them.

Footnotes

1: Some professional academic organizations, like the Association of Internet Researchers (AoIR), have published guidelines for working with internet data: https://aoir.org/ethics/

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: